The Detroit building that took 25 years to complete

No, not Perfecting Church on Woodward. Here's the tale of an Art Deco social club that broke ground in 1928 and didn't open until 1953 as an apartment building.

Here's how a social club's grand plans led to the city having a "ghost skyscraper" for more than two decades, long before Detroit's misfortunes left it littered with them. Below is the Reader's Digest version. The unabridged version, with more photos and renderings, can be found here on our website, if you want to read the whole saga.

The Town Residences is proof that good architectural things come to those who wait - and wait and wait. This building sat unfinished, a ghost-like, windowless shell on the fringes of downtown, for more than two decades. You could call it Detroit’s own Sagrada Família.

The 13-story, Art Deco-style tower came off the drafting table in 1924 as a clubhouse for the National Town & Country Club. As its name implies, the club was a nationwide social organization, and was started in the 1920s in New York City. One of its selling points was that members of one chapter had privileges at the others around the country. Of note, the group was far more inclusive than most other social clubs of the era, with Black, Jewish and Catholic members being invited to join, though not women unless they were the widow of a life member. By comparison, organizations like the Detroit Athletic Club would not allow women, Jews or African Americans to join.

The Detroit chapter of the National Town & Country Club was founded in 1924. Lifetime membership fees were $15,000, a tidy $278,000 in 2025 valuation, when adjusted for inflation. But Detroiters, being flush with auto cash, were good for it: Just four years after its founding, the local chapter had about 2,000 members, with membership limited to 3,000.

This building was developed by club President Edward A. Loveley’s real estate company, Stormfeltz & Loveley, and designed by boardmember H.J. Maxwell Grylls' firm Smith, Hinchman & Grylls. Its lead designer was Wirt C. Rowland of SHG, the same man behind the Guardian, Buhl and Greater Penobscot buildings, among other landmarks in the city.

Social clubs were all the rage in the Roaring Twenties, and Detroit was home to a number of them, most of which were aimed at the so-called Gasoline Aristocracy that rose to wealth during Detroit’s emergence as the Motor City.

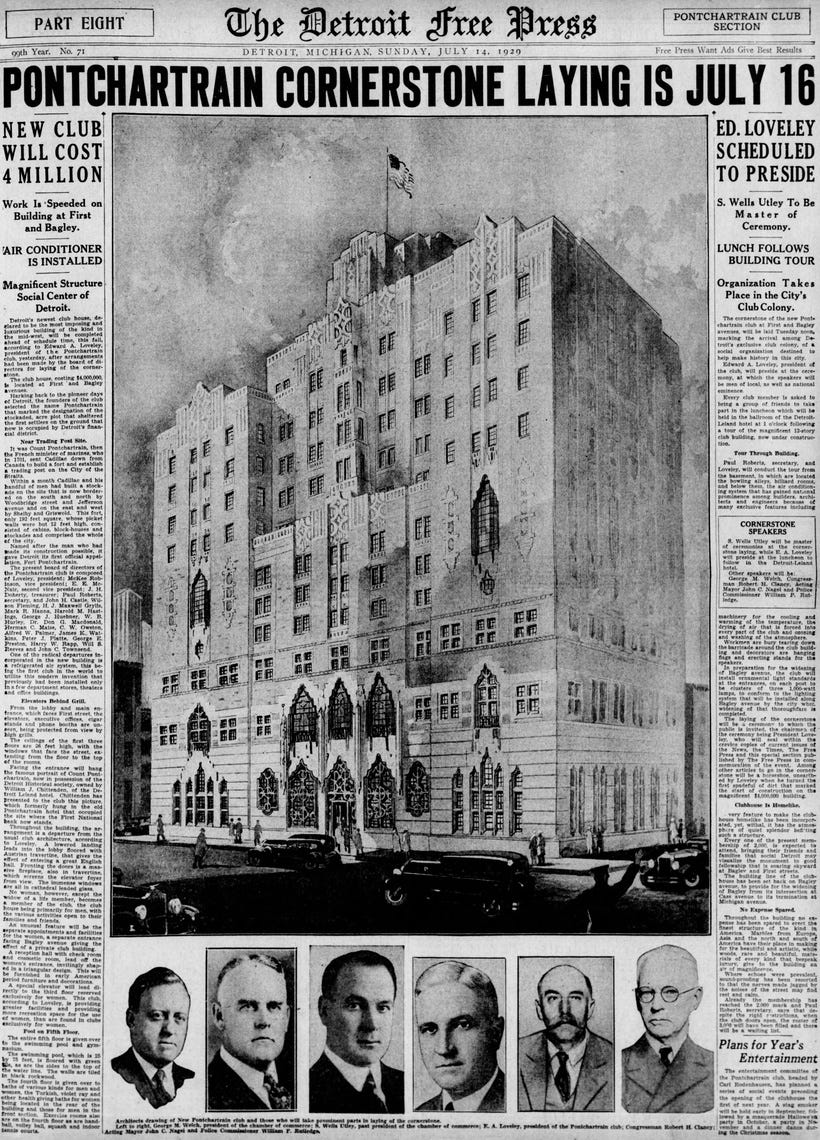

“Born in the minds of a group of prominent Detroit clubmen, the idea was based on the fact that the old exclusive clubs are crowded and each has a long waiting list,” the Detroit Free Press wrote July 14, 1929. “The Pontchartrain was to open its doors to this eligible list who were denied membership in other exclusive clubs through lack of facilities to accommodate them.”

Meanwhile, Stormfeltz & Loveley set its eyes on turning Bagley Avenue from a bunch of Victorian-era homes and commercial buildings into a hustling and bustling economic center. The National Town & Country Club Building would be near the heart of it all. Stormfeltz & Loveley formed the Detroit Properties Corp. (DPC) to lead the work, which was said to represent $35 million in investment, the equivalent of $645.2 million in 2024, when adjusted for inflation. The new clubhouse alone would account for $4 million of it, about $74.1 million in 2025. Among the properties DPC built as part of the so-called Bagley Avenue Development project were the Michigan Theatre Building, United Artists Theatre Building and Leland Hotel. Bagley Avenue was also widened as part of the makeover, from 40 feet to 90 feet.

The Town & Country name is put out to pasture

On May 4, 1929, the National Town & Country Club rebranded itself as the Pontchartrain Club.

The Pontchartrain name is one that traces back to the founding of the city itself in 1701. Detroit's founder, Antoine de la Mothe Cadillac, went to Count Pontchartrain - the French minister of marine affairs - to get permission to explore the Great Lakes. He told the count that if the French didn’t secure the region, the British would. That’s all the count needed to hear, and he gave Cadillac the thumbs-up. Cadillac and his band of merry hommes established an outpost on the straits of what is now the Detroit River. In an impressive feat of brown-nosing to his sponsor, Cadillac dubbed the outpost Fort Pontchartrain du Détroit: Fort Pontchartrain of the Strait.

“When the new $4 million clubhouse reaches completion and assumes its place in the social and recreational life of the city as the Pontchartrain Club, it will stand as a permanent memorial to the man who furthered the first settlement and development of Detroit,” Loveley said of the count, in a May 5, 1929, article in the Detroit Times.

What would have been

The clubhouse was to feature a number of amenities - such as athletic facilities, eight bowling alleys in the basement, a billiards room on the mezzanine overlooking the lobby, a library and dining rooms - on the lower floors and four floors of sleeping quarters above for members and overnight guests, 96 rooms in all. The fourth floor was to house Turkish baths, as well as courts for squash, handball, volleyball, indoor tennis and badminton. Massage, needle baths and electric cabinets for ultra-violet ray treatments were also to be provided. The swimming pool, measuring 25 feet by 75 feet, was to have been on the fifth floor.

“From every corner of the civilized world, material has been gathered to make the Pontchartrain the most luxurious, modern and beautiful building of its kind in the world,” the Free Press continued. “Africa has given its rarest woods, ebony, mahogany and others - the Far East, stains, shellacs and rare colors - South America, daintily tinted stones - the Russian Steppes, marbles - each country has contributed of its best toward this citadel to the social side of man whose cornerstone is fellowship and brotherly love.”

In what the Times described as “unusual provisions … made for the wives and families of members,” the third floor was to be devoted to female guests and the wives of members. It was reachable by a dedicated private elevator and complete with a ladies dining room, beauty parlor, library, lounge and reception room.

“Facilities of the new Pontchartrain are so cleverly arranged that women or men may enter and leave the building, enjoying therein the full advantages of the club’s various departments, without encountering members of the opposite sex,” the Free Press wrote July 14, 1929.

A groundbreaking was held at 12:15 p.m. on Sept. 5, 1928, with Loveley, being the club’s chairman, doing the honors of turning the spade. Steel work followed Dec. 1, 1928, when a gold-plated rivet became the first driven into a girder as part of that day’s festivities. On June 8, 1929, the Detroit Times reported that work was continuing to progress rapidly. Things would not move as quickly in the decades to come.

Meanwhile, in the first hint of possible trouble, the cost of the building was reduced to a more modest $2.3 million, or about $42.9 million in 2025 inflation-adjusted figures – a cost-cutting of $32.2 million in modern times. The club was said to have raised $2 million of that $2.3 million by the time the building’s cornerstone was laid on July 16, 1929.

Inside the cornerstone were placed copies of the three daily Detroit newspapers of the day, photos of the prominent promoters of the club, stationery, letterheads, a membership brochure, a list of members, membership cards, a copy of the club’s by-laws and a horseshoe that had been found while excavating the site of the building.

It would turn out that the horseshoe wasn’t of the lucky variety.

Unfinished business

But with the exterior completed, work on the clubhouse ground to a standstill in 1929. The Wall Street crash of that year led to the Great Depression, which in turn led to the Pontchartrain Club being left a beautiful but unfinished, windowless shell for more than two decades. Later news reports said the building was 73 percent completed at the time work stopped, and at least $2.5 million had been spent on it, about $47.5 million in 2025. Its members would get nothing to show for their financial contributions to the project, as the Pontchartrain Club soon folded.

Over the next nearly two decades, the building would be floated as everything from offices for a railroad system to a veterans headquarters to a City-County building to apartments to a hotel.

After a series of unkept development promises, The Detroit News Editorial Board opined on Oct. 7, 1938, that “we do urge that when the property finally comes into the City’s possession because of tax delinquency, the skeleton building be torn down. For years, it has stood in its ghostly emptiness, a too-noticeable reminder of an unfinished task in a city which boasts of its ability to finish whatever it undertakes.”

Then World War II and war-time rationing arrived on the Depression’s heels.

The State Land Office Board seized the building over delinquent taxes in November 1939. No taxes had been paid on it for more than a decade, and with no credible suitors to buy it, the State rented its ground floor out as a storage lot for new cars, collecting $145 a month in rent, about $3,300 in 2025. In early February 1941, talks began about the State completing the Pontchartrain Club for use as a state office building, a plan pitched by Auditor General Vernon J. Brown that he said would cost about $1 million ($22.8 million in 2025).

“The State would make a worthwhile investment if the plan goes through,” he told The Detroit Times for a Feb. 20, 1941, story. “The building is adding no value to an already blighted area. If it could be used for State offices, the valuation of surrounding properties would rise and result in more revenue for the State and City. For us, it would be an ideal location.”

He also noted that the State was spending nearly $80,000 ($1.8 million in 2025) a year in rent on office space in Detroit alone, so a State-owned building would pay for itself in 12 years.

But he needed approval by the state Legislature. He wouldn’t get it. The club would continue to sit, a giant pigeon coop and indoor parking lot.

If at sixth you don't succeed ...

On Sept. 7, 1944, The Detroit News Editorial Board weighed in yet again, calling the “one of the world’s largest haunted houses. … No one has inhabited it; it is haunted only by the problem of its eventual utility.”

Then on Sept. 20, 1947, a syndicate of out-of-town businessmen announced that it had purchased the building for more than $250,000 (about $3.5 million in 2025) in order to turn it into office, manufacturing and warehouse space.

“The biggest skeleton in Detroit’s closet is about to disappear, and there will vanish with it a symbol of a long-departed dream,” George W. Stark wrote in the Detroit News on Sept. 26, 1947. “For years, (the Pontchartrain Club) has stood at Bagley avenue and First street, rearing its rococo elegance a full 13 flights skyward, windows open to every boisterous gust, with nary a tenant, except, perhaps, the vain regrets of its original promoters. …

“The Pontchartrain Club has been, through all the years since 1928, a stark and dreary token of the postwar Depression, a bitter reminder that there is an end to the rainbow and no pot of gold to distinguish it.”

Work was to start by the end of the year. It didn’t.

In October 1949, the Pick Hotel Corp. of Chicago (which ran the Fort Shelby Hotel in Detroit at the time) announced it would turn the 13-story skeleton into 322 two- and three-bedroom apartments in a $3 million conversion ($40.6 million in 2025).

The Detroit News Editorial Board was optimistic, writing Oct. 20, 1949: “The Pontchartrain Club has been for years, despite its architectural merits, a leading eyesore. Its tenantless, gaping windows have been a reminder both of the lush day that gave birth to the club project and of the bitter season of blasted hopes that followed. … The Pontchartrain project, if it proves profitable, might lead to others and conceivably could start a movement reversing in some measure the march of population to the suburbs, now a real threat to Detroit’s future.”

If they only knew. Meanwhile, unsurprisingly, Pick bowed out.

Following World War II, there was a tremendous demand for housing, both because of the soldiers returning home and also because of the lack of building during the conflict because of rationing. On top of that, Detroit’s economy and population were booming; after all, the city was known as the Arsenal of Democracy, and a number of people moved to the city for the bountiful manufacturing jobs in the defense plants.

But Detroit was also facing another issue: Much of its housing stock and apartment buildings were older, and areas of the city had become both overcrowded and rundown because of the double-whammy of the Depression and wartime rationing. On top of that, much of the post-war housing boom was occurring in the suburbs. That said, there were still plenty of folks who preferred to live in the big city, especially downtown, but there really weren’t many options at the time, especially modern ones with central air-conditioning, electric appliances, fluorescent lights and other innovations that were in high demand.

All of these circumstances combined to make completing the forlorn Pontchartrain Club financially feasible, more than two decades after work had stopped on it.

A delayed dream, finally finished

On Nov. 1, 1950, it was announced that the building had been acquired by a group of out-of-state businessmen under the name Bagley First State Corp. The purchase price was $550,000, about $8.2 million in 2025, and the plans called for the new owners to drop $3 million ($39 million in 2025) to turn it into a 318-unit apartment building.

The difference-maker this time around was that the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) insured a $1.8 million ($23.5 million in 2025) loan for the project, where it had previously refused other bids to do so. Perhaps its mind was changed by Detroit’s housing shortage.

The Cuyahoga Wrecking Co. of Cleveland was tapped to “clear away elaborate stairs, piping and conduits,” The News wrote March 7, 1952, as well as tons of concrete damaged by the weather pouring into the building since 1929. Workers on the site found a number of unopened crates of materials lying around throughout the building, containing overalls, shoes and tool boxes.

The job was to take 18 months. Strikes and material shortages caused delays.

As part of the renovation, the building’s exterior was altered. Window openings were significantly enlarged, and the lower floors were refaced with what the National Register of Historic Places nomination calls “a streamlined look of the early post-World War II period.” The building’s basement was turned into an underground, 25-car parking garage, which is entered through a garage door along Bagley Avenue.

Finally, in August 1953, the job was done, 25 years after ground was broken. The Pontchartrain Club opened as the Town House Apartments. It’s unclear whether this was a nod to the club’s original name of the Town & Country Club, but it appears to be a coincidence.

Rents were to be from $115 to $125 a month for the unfurnished studios to $225 to $250 for three-room units. That’s the equivalent of about $1,400 to $1,500 and $2,700 to $3,000 in 2025, respectively.

Perks included terrace decks where residents could sunbathe, high-speed elevators that climbed at 400 feet a minute, all-electric Pullman kitchens, and 16 penthouse-type units on the 13th floor (eight of those had doors opening onto the terrace). The two-room efficiency offered a living room with recessed all-electric kitchen, a dressing room with built-in dressing table and a bathroom. The three-room added a separate bedroom. The kitchens in both models were recessed and able to be hidden behind a traverse drapery. The apartments came either furnished or unfurnished, and tenants had their choice of wall colors from blue, cocoa, gray, green or pink.

“Our first tenants all are top executives who work in the area of the building and want to live near their work,” part-owner Hal D. Cantin, told the Detroit Times for an Aug. 9, 1953, story. “Others have moved here from Detroit’s principal hotels. They are older people, mostly, including several who took part in the original plans to build the Pontchartrain Club.”

All quiet on the west side front

In the 1980s, the building’s name was tweaked to the Town Apartment Tower. It continued to offer studio and one-bedroom apartments, both furnished and unfurnished. Amenities at the time included a uniformed doorman, a cafe, on-site laundry facilities and a fitness center.

In May 1999, the Hayman Co., still the building’s owner at the time, announced that it would convert some of the apartments into a Hawthorne Suites hotel over a six- to 12-month span. At the time, 140 of its units were unoccupied.

“We’ve owned the building for 27 years, and some residents have been there the entire while,” William Humphrey, a Hayman operations vice president, told The Detroit News for a May 19, 1999, article. “We intend to have a section of the property maintained as extended-stay and apartment-style, so it'll be a gradual change. As demand builds for hotel rooms, it'll behoove us to convert more. Initially, we may only have 150 of 315 units designated as hotel accommodations.”

Like so many plans for this building, that didn’t happen. Instead, Hayman was approved by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) to accept housing vouchers that paid a portion of lower-income tenants’ rent. In the early 2000s, rents ranged from $465 to $1,000 per month for one of the penthouses. Those with the housing vouchers paid only a percentage of their income out of pocket.

In July 2014, the building was sold to Colorado-based Triton Investment Co., which embarked on a $5 million renovation that saw the lower-income rents replaced by market-rate ones. Walls were knocked down to combine units, and its 318 apartments now number about 250. Its name was changed ever so slightly once again, to the Town Residences.

Triton planned to install new kitchens, appliances, lighting, paint and flooring in most of the units, as well as upgrade the laundry room and fitness center while adding bicycle storage. A new front awning, signage and windows were added to the building’s exterior.

Detroit-based Kraemer Design Group, which has had a hand in a number of historic renovations and restorations in the city, served as the project architect. ROK Construction Services, also based in the city, was the general contractor.

Rents were increased to $695, including utilities, for a studio and up to $1,195 for a two-bedroom.

“Detroit is a great story, the city is coming back, and we see a lot of opportunity for people who want to live in historically-significant properties,” April Sedillos, executive vice president of Triton, told DBusiness Magazine for a Sept. 4, 2014, article.

Perhaps this building’s story gives hope to Detroit’s other notoriously delayed project, the Perfecting Church. That one, at Woodward and 7 Mile, is now at 21 years since construction began, so it needs only a couple of more to catch up to the Town Residences’ infamous record.

Super awesome job with this complex history. The Town Apartments could have been demolished over the years, but it survives and thrives today!