The forgotten Detroit rollerskating rink that changed the sport forever

The Arena Gardens hosted everything from opera singers to presidents to alligator wrestlers, but it has a legendary status among rollerskating buffs

When you think of how Detroit put the world on wheels, most folks think of the automotive industry. But there was another institution that played a key role in helping to get our country rolling.

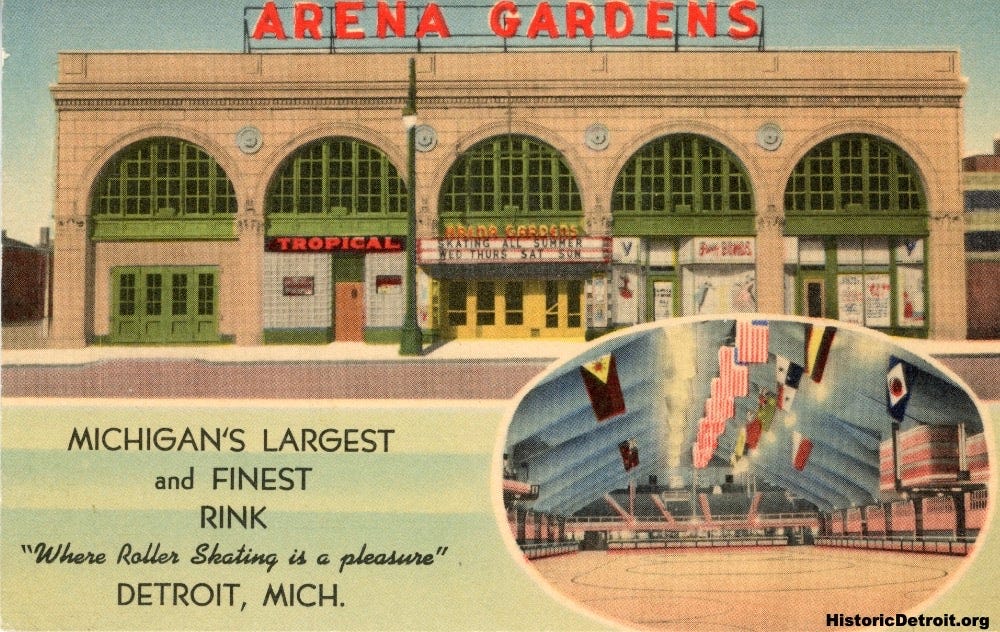

The Arena Gardens was a legendary rollerskating rink, so much so that the National Museum of Roller Skating in Lincoln, Neb., put out an entire book on the venue in 1999 called “The Allure of the Rink: Roller Skating at the Arena Gardens.”

“From 1935 until it closed in 1953, the Arena Gardens captured the loyalty of both the people of Detroit and of the thousands of Americans who visited,” author Sarah Webber wrote. “This celebrated roller rink, so completely designed and organized around providing roller skaters with a wholesome and enjoyable experience, represented then, as now, the paragon rink in the era of roller rink skating in the United States.”

But its eclectic history stretches far earlier than its rollerskating heyday, as the venue served as everything from a ballroom to a concert venue and a shopping mall to a car wash; it hosted everything from auto shows to ice skating to boxing; and hosted everyone from former U.S. presidents to military generals to opera stars to alligator wrestlers.

Thin ice

The Arena Gardens’ roots are tied to Detroit’s first artificial ice rink, the Detroit Arena, which opened Dec. 3, 1910, on East Warren Avenue near Riopelle Street. It was the brainchild of Harry and David A. Brown, die-hard hockey lovers who sought to popularize the sport in Detroit. The brothers operated the General Ice Delivery Co., which made and sold ice in an era long before your fridge did it for you. The 20,000-square-foot rink could accommodate 3,000 skaters at one time, and its grandstand could seat 3,000 people.

However, the rink’s “chief handicap,” the Detroit Evening Times wrote Jan. 21, 1913, was that it was too far from Woodward Avenue, the city’s main thoroughfare.

Therefore, the Browns secured options on several available sites along Woodward, “so that when the time is ripe for an artificial ice rink on Detroit’s main stem, the Brown family will have the whip,” the Evening Times wrote. “It seems certain that there is destined to be a paying rink on (Woodward) Avenue. … (Harry) Brown has watched dance balls, theater and other places of amusement being built along the big trail, and he is not unaware that that is the ultimate location for his rink. Once it is there, the popularity of hockey will have no bounds, is his prediction.”

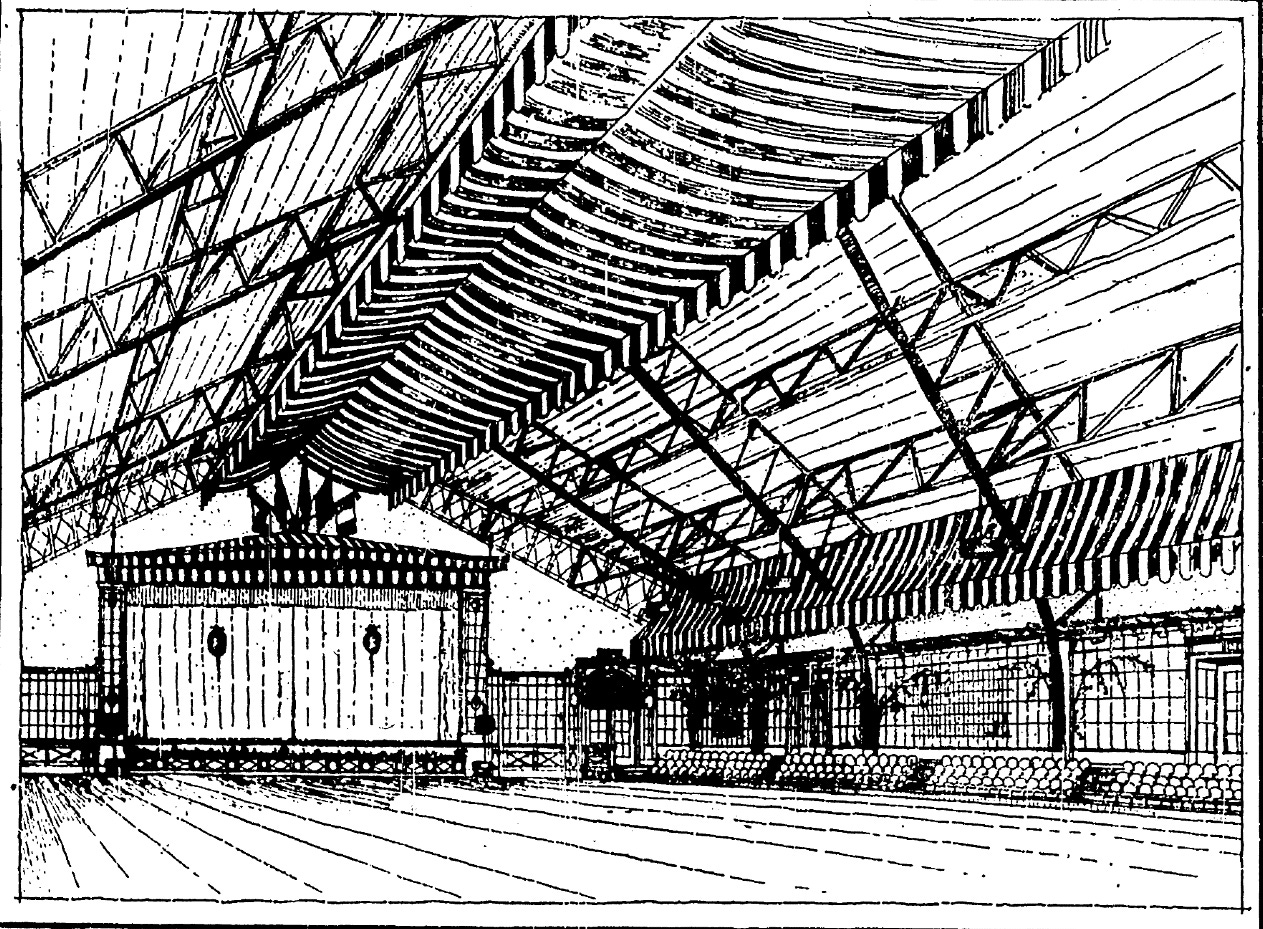

Finally, in the summer of 1916, that vision would start to become a reality as workers broke ground on the project. Brown had hired famed Detroit architect Albert Kahn to design a huge new auditorium of steel and reinforced concrete on the west side of Woodward Avenue near Hendrie Street. The building was long but narrow - 100 by 470 feet - and stretched from Woodward the entire block, to Cass Avenue. Brown’s plan was to use the building as an auditorium capable of holding up to 10,000 people from April to November and convert it into an ice rink during the winter months. It would have about 2,500 permanent seats for hockey games, with 900 on the main floor and 18 rows of seats in the balcony.

Kahn coated the exterior in white terra cotta, and utilized a steel truss system to keep pesky columns out of sight lines and out of the path of ice skaters.

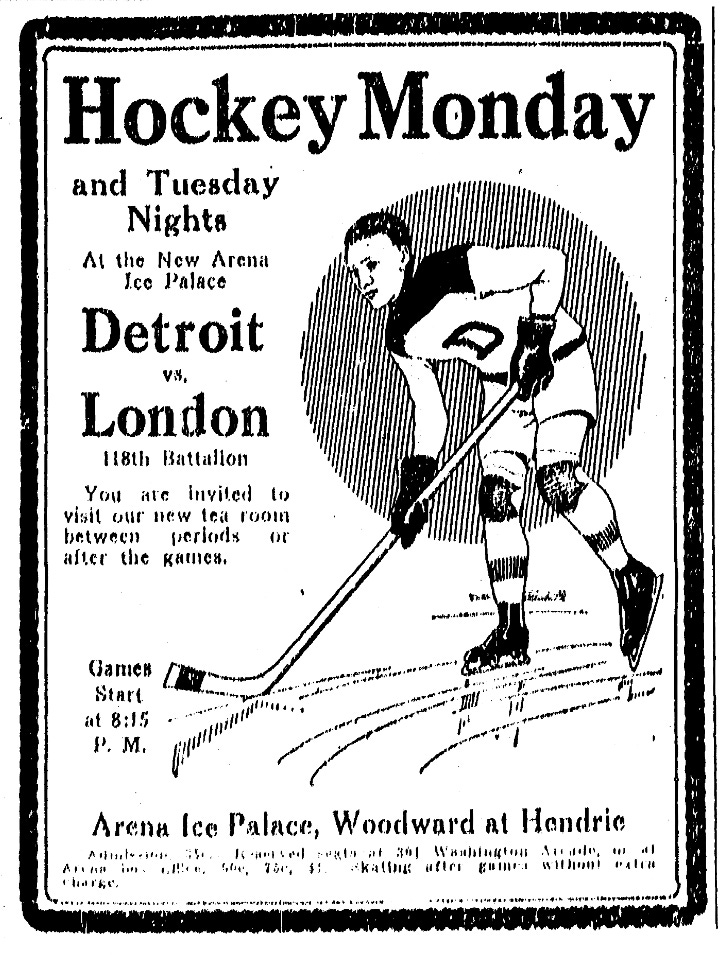

The Detroit Hockey Club was granted use of what was then being called the Detroit Arena Ice Palace for its upcoming season, but the arena wouldn’t be ready to go until mid-December 1916. Games were held on Monday and Tuesday nights. The DHC was led by stars like Al Roberts, “Spider” Johnston and Rover "Speed" Holman; the men wore pink and white uniforms while squaring off against teams like the Toronto Crescents and the Kitchener (Ontario) Union Jacks.

“The game of hockey has enjoyed a rather checkered existence in Detroit,” The Detroit News wrote Dec. 3, 1916. “The teams of 1910-11-12-13-14 played good hockey, but patronage was lacking due to the poor location of the rink. Then two seasons ago, the Detroit Hockey Club organized, taking hockey in its own hands, and its success seemed assured. … This season, the D.H.C. has made arrangements to use the new Arena rink, which has everything in the way of accommodations that the game should need to make it flourish. … Plans are being made to bring the best hockey teams of Canada and the United States here in the expectation that Detroit now is ready for ‘big league’ hockey and will support it.”

After the rink was disassembled for the season in March 1918, the Arena would host ballroom dancing and a series of philharmonic concerts. But without any reason given in the newspapers, management decided to go in a different direction. In June 1918, it was announced that the ice arena would become a concert venue and dance hall full time.

And that was a shame for the hockey club because, as The Detroit News reported Jan. 9, 1918, they had finally managed to win over the city’s fans. Under a headline reading: “Strange sight witnessed: Detroit hockey team cheered,” The News reported that “when the Detroit hockey fans began cheering their own team Tuesday evening, it almost marked a new era in Detroit hockey.”

But left without a home, the team was disbanded. That new era in Detroit hockey would have to wait until the Red Wings arrived in 1926.

Detroit’s Gardens

The venue would undergo a major transformation, and such a transformation called for a new name: the Arena Gardens.

Famed theater architect C. Howard Crane was hired and “authorized to spare no effort in making it one of the best in America,” The Detroit News reported June 23, 1918. Crane is best known for his designs that would come after the Arena Gardens, such as the Fox Theatre, Fillmore Detroit and what is now the Detroit Opera House.

The Arena was said to have already proven to have “perfect” acoustics, so all it really needed was to be gussied up. A 40-by-80-foot stage for concerts was set up on the Cass Avenue end and was deemed one of the biggest in the state. When not hosting concerts, the venue would be open for dancing on an 18,000-square-foot dance floor that was said to be the largest in the Midwest.

The arena’s interior was done up, as the name would imply, like a summer garden. On the sides, lattice work was covered in climbing vines. Red- and white-striped canvas hung from the ceiling, providing a canopy effect.

The Arena Gardens formally opened with a night of dancing to the 15-piece Arena Gardens Orchestra on Sept. 7, 1918. Several hundred guests turned out to help break in the dance floor. Admission was 10 cents for women and 15 cents for men, the equivalent of $2 and $3 in 2025, respectively.

The stars descend on the Arena

Its first concert was held Sept. 30, 1918, with opera singers Carolina Lazzari of the Chicago Opera and the Metropolitan Opera Company’s Frances Alda, Giovanni Martinelli and Giuseppe De Luca. Other artists performing in the venue’s first philharmonic season included Jascha Heifetz (billed as “the greatest violinist of the century”) and Hipolito Lazaro, “the sensational Spanish tenor of the Metropolitan.”

On Nov. 11, 1918, the Arena Gardens hosted a recital by famed Italian coloratura soprano Amelita Galli-Curci, which was said to be the largest concert audience in the city’s history up to that point, though no attendance figures for that show were given. Crowds of more than 4,500 were reported at other concerts held at the venue, so it is assumed the number of attendees that night was higher.

The Detroit Free Press review the following morning glowed that “every seat in the large auditorium held its Galli-Curci devotee or an expectant, curious person who, before the evening was over, became as eloquent in praise of the singer as those upon whom she had cast her spell in previous visits to the city.”

John Philip Sousa - the American composer of “The Stars and Stripes Forever” fame and the so-called “king” of the military march - would bring his band to the Arena Gardens, for two performances on Oct. 12, 1919.

On May 16, 1919, former President William Howard Taft addressed an audience at Arena Gardens about the importance of creating the League of Nations, telling Detroiters that the “desire for the League of Nations springs from the people who have been through the vortex of war and who do not want to pass through it again.”

“Detroit surrendered gladly to Gen. John J. Pershing” at the Arena Gardens on Dec. 18, 1919, the Detroit Free Press reported the following morning. The commander of the American Expeditionary Forces (AEF) during World War I spoke to 8,000 Detroiters that night, telling them that it was his belief that the struggle of classes would be settled by “the rich boy and poor boy who elbow to elbow in Europe learned the value of combined action as opposed to independent action and found admirable qualities in each other.”

From venue to market

It is unclear whether all these elaborate productions were unprofitable or someone outbid the Gardens’ operators when it came time to renew the lease, but just two years later, it was announced that the Arena Gardens was being transformed from “a place of amusement to a market building,” the Free Press wrote Sept. 15, 1920.

One hundred workmen on three shifts stripped the Arena Gardens of its finery. The fine hardwood floor was ripped out and replaced with concrete and tile. Rows of chairs were replaced with rows of stalls. Some $250,000, the equivalent of $4.2 million in 2025, when adjusted for inflation, was spent on the conversion.

The building was leased to the Detroit Markets Co. and renamed the Cass Woodward Market. It featured more than 80 food shops on the main floor and 30 shops on the second-floor balcony arcade, including clothiers, music, hardware and shoe stores. In all, 70,000 square feet of retail bliss made it something of a precursor to the shopping mall. It was said to be the largest establishment of its kind in the Midwest.

This venture would prove to be short-lived, because in the fall of 1923, it was announced that dancing would return. A gala reopening was held that Sept. 7.

Concerts were brought back, too, including a gig by the 53-member Sistine Chapel Choir. The Arena Gardens would host a bit of everything else in between, from indoor baseball tournaments to temporary bowling alleys to Vaudeville to fashion shows to circuses to political rallies. It also brought back boxing - lots of it, often weekly. The great Sonny Liston fought at the Arena Gardens in front of 2,000 fans.

One of the more dramatic events held at the Arena Gardens was an anti-Ku Klux Klan rally on Oct. 21, 1924. Aldrich Blake, an anti-Klan force from Oklahoma, delivered a speech while thousands outside tried to drown him out by shouting and honking the horns on their cars. A mob of 6,000 supporters of Detroit mayoral candidate Charles Bowles - who had been backed by the KKK - tried to impede folks from attending the rally. Police had to resort to tear gas to break up the mob. Though they dispersed, Bowles supporters then took to their automobiles and started a parade going around and around the block, not leaving until Blake’s event was over. If any arrests were made, they were not reported in the papers. It was national news, even being covered by The New York Times. Bowles refused to comment on the near riot, but decided to hold a campaign rally at the Arena Gardens himself, on Nov. 4, 1924.

Bowles lost that election, but would become the city’s 58th mayor in 1930. He was recalled from office just six months later over corruption and for tolerating lawlessness in the city.

It’s unclear whether the venue’s operators went bust, but on July 30, 1928, the Arena Gardens was reopened as the Arena Gardens Automobile Laundry. Detroiters could drive into the building, get their car washed "inside and out in jiffy time" for 95 cents and then drive out the other side. Patrons could hit up the soda fountain, watch the work being done on their car or kick back and relax in a spacious lobby.

This venture also apparently proved unprofitable, because in July 1930, the Union Guardian Trust Co. advertised that the Arena Gardens was "available for immediate possession at a most attractive price."

It would find a buyer in former wrestler and sports buff Adam Weismuller.

The wrestler’s Arena

Weismuller was born in Vargas, Romania, and came to the U.S. around the age of 14, with his family settling in Chicago. There, he became a member of a turnverein, a German gymnastic troupe. Wrestling caught his fancy, and before long, he was facing off with the "matmen." He moved to Detroit in 1924, and the following year, became the American welterweight champion. This was not Hulk Hogan's style of wrestling; some of Weismuller’s matches lasted up to two hours.

In the late 1920s, when Weismuller was at the peak of his wrestling career, another grappler approached him, seeking help. The other man was suffering from trachoma, a contagious bacterial disease that often causes blindness. Because no other wrestler would square off against him over fears of catching it, the man was penniless and in debt. He begged Weismuller for a match.

"Weismuller wrestled with him to help him out, and today is paying the penalty of his charity," the Detroit Times wrote Aug. 17, 1930. Weismuller "is doomed to end his career in a pall of darkness. He is going blind. His left eye already is sightless, and specialists tell him that he will lose the vision of his right eye. His disability has cost him his job, and his savings have been exhausted in doctor bills. Wrestling caused Weismuller's blindness, and from wrestling, he hopes to salvage something of the wreckage of his life."

He did that by taking up sports promotion and organizing a wrestling league. Along with Jim Londos, known as "the Golden Greek," wrestling was about to enter its golden era in Detroit. Wrestlers like Ali Baba (catchphrase: “Is he man or beast?”), Nango Singh, Man Mountain Dean, Lem Tunney, Bert Ruby and the Masked Marvel dazzled Detroiters in the 1930s and early '40s. Weismuller "became a sort of legend, a reputed King Midas of his little domain," the Detroit Times wrote March 9, 1937.

While the Depression was pinning the local and national economy, Weismuller took over the Arena Gardens in 1930, offering wrestling every Monday night. Seating capacity for Weismuller’s events was about 4,700, and he also held outdoor matches in a ring set up on property adjacent to the venue.

From 1933 to 1937, his wrestling troupe performed to large crowds and led Weismuller to branch out to Pontiac and Lansing, as well as Chicago; Columbus, Cincinnati, Cleveland and Dayton, Ohio; Louisville, Ky.; and Milwaukee, among other cities.

With his skillful promotional tactics and newfound change of luck, Weismuller decided to expand the venue’s offerings in order to keep the place busy throughout the week instead of only on Mondays for wrestling. In September 1936, he joined forces with Louis J. Giffels, the general manager at Olympia Stadium, to promote boxing matches at the two venues.

On Oct. 31, 1934, the legendary Joe Louis made his one and only appearance at the Arena Gardens before a crowd of about 1,000 people. It was the ninth bout of his pro career, and he floored Jack O’Dowd for a nine-count in the first round before knocking him out in the second.

But Weismuller’s biggest move was deciding to also add rollerskating to the menu.

Wheels up

In 1910, there were only about 150 rollerskating rinks across the country. Though the pastime had experienced a surge in popularity in the late 19th century, it had fallen out of favor as rinks became notorious hangout spots for ruffians and thugs - as odd as that may sound today. With the onset of the Depression, more and more out-of-work Americans were looking for something fun - and most importantly, cheap - to do.

The trouble was, Weismuller didn’t know the first thing about operating a rink. He reached out to Fred A. Martin, the general manager of Chicago’s White City Rink, for advice. Martin had developed a lifelong passion for a life on wheels working at a rink in San Francisco, where he was raised. He took up speedskating and began racing competitively while a teen. In 1914, he won the world's 24-hour endurance speed-skating title, one he hung onto until 1920, when he gave up racing in order to focus on the business side of the sport. Following a meeting with Weismuller, the Martins moved to the Motor City in the late summer of 1935.

The family got to work helping Weismuller turn the Arena Gardens into a rollerskating Mecca. Central to the makeover was a new 25,000-square-foot maple floor measuring 88 by 240 feet, with the wood at the both ends of the rink angled at 180 degrees to ensure that the skaters’ wheels always followed the grain. Weismuller also installed a three-console Wurlitzer pipe organ, complete with all the bells and whistles, as well as horns, chimes, bells and trumpet sounds that were found in traditional theater organs. After all, what was rollerskating without music?

But a year and a half after rollerskating began at the Arena Gardens, Weismuller died at Henry Ford Hospital, on March 8, 1937, succumbing to a stomach disorder. He was just 37 years old.

"Weismuller's record as a promoter stands as a tribute to persistence that few men in any sport can match," The Detroit News wrote the day of his death.

"The grunt and groan industry won't seem the same here without him," the Detroit Times added March 29, 1937.

Martin was put in charge of day-to-day operations of the Arena Gardens, effectively putting him in control of the place. He would ensure that the skating business kept the venue’s doors open.

After becoming manager, one of Martin’s first moves was to establish the Arena Gardens Roller Skating Club, in 1935, to build the number of regulars and create a social club of sorts to keep folks coming back. Members got discounts on admission, invitations to members-only events and a monthly newsletter, the Detroit Roller Skater. Within a year, it had 2,000 members, and by 1940, had grown to 5,000.

Respectability at the rink

On April 4, 1937, Martin persuaded 16 owners who operated 23 rinks across six states to form the Roller Skating Rink Owners Association (RSROA) in order to set a new standard in the business. By the end of the year, the RSROA had more than 100 members.

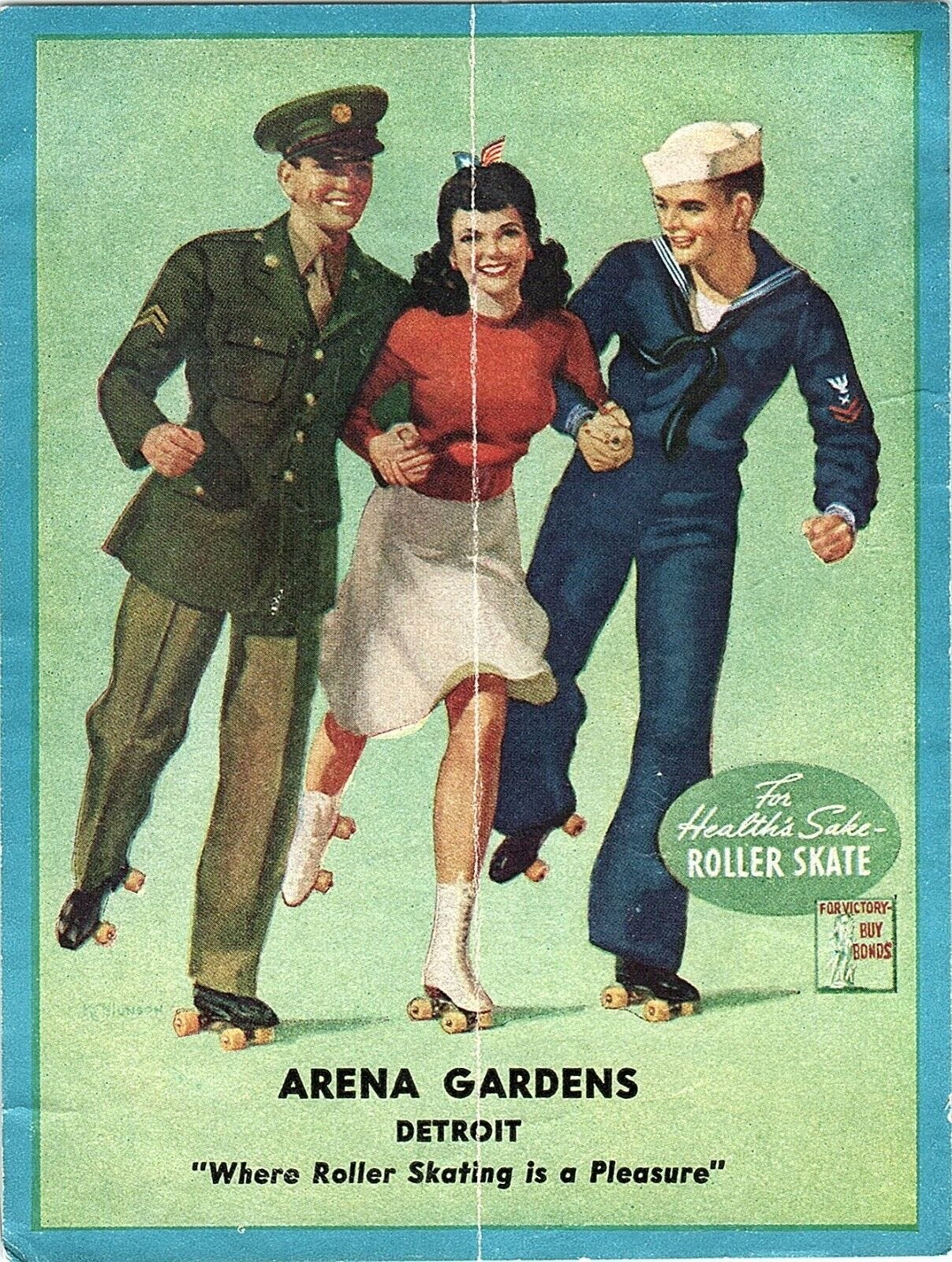

Rinks in the RSROA kicked out the troublemakers and implemented strict, formal dress codes. At the Arena Gardens, men had to be in dress pants or slacks, dress shirts and a tie; women had to wear dresses or skirts that reached at least the knees. Throughout its entire existence, the Arena Gardens never allowed jeans, T-shirts, collarless shirts or sweaters. By requiring skaters to dress formally, as they would for other social events, Martin believed he was instituting a policy of civility and keeping crowds from becoming rowdy or disrespectful. While a doorman would greet each patron warmly, those with booze on their breath were not allowed inside. Anyone who was a bully on the lanes, or cut other skaters off, was told to leave.

Likewise, employees all had to dress sharply in red uniforms with white hats and gloves. The management always wore tuxedos, which Martin said helped visibly demonstrate that the Arena Gardens was a respectable place. The Arena Gardens had both Black and white employees. However, Webber’s book notes that few African Americans were known to have actually skated there, perhaps because of economic reasons or feeling socially unwelcome.

In 1942, admission was 50 cents for Arena Gardens Skating Club members and 60 cents for the general public, or about $10.25 and $12.30 in 2025 valuation, respectively.

Because many Detroiters did not own their own skates, especially in the early days following the Depression, the Arena Gardens rented out clamp-on skates that attached to their shoes. By the early 1940s, the rink switched over to renting out skates with boots attached. Guests were directed to the skate room, where attendants not only provided patrons with a pair of skates, but skate boys to put them on for them.

If a customer was new to rollerskating, Martin called over an instructor to help them get the hang of it on a 4,000-square-foot practice rink before turning them loose on the main floor. Professional instructors also offered private lessons for $1 an hour in the 1930s (about $22 in 2025) and $2.50 in the 1940s and ‘50s (about $50 in 2025).

Martin was so committed to ensuring the Arena Gardens was the best around, he even micromanaged to the point of making sure the refreshment counter’s milkshakes were up to snuff. Other refreshments on offer included sundaes, Boston Coolers and hot dogs.

By 1955, there were more than 5,000 Detroit-area skaters registered to compete in official competitions, and a number of Arena Gardens skaters took home trophies. The Detroit News wrote Jan. 7, 1952, that “as far as rollerskating is concerned, Detroit has for years been the City of Champions, and Arena Gardens the Cradle of Champions."

This helped rollerskating become the second-most popular participant sport in the country next to bowling. Americans bought three times as many rollerskates as ice skates in the 1930s, according to the National Museum of Roller Skating, and by 1942, there were more than 3,000 rinks across the country - an increase of 1,900 percent over 30 years. It was estimated that more than 10 million Americans were lacing up their skates, and by 1940, some 6,000 Detroiters were heading to the Arena Gardens each week.

On the wrestling side, beefy behemoths like Hombre Montana, Pancho Romero, Super Mr. X, Ivan “The Terrible” Rasputin, Chief Lone Eagle, Flash Clifford, the Hungarian Angel, Louie Klein, Buddy “Nature Boy” Rogers and Bozo Brown took to the mat at the Arena Gardens in this era. On Nov. 9, 1948, a heavyweight wrestling bout at the Gardens also featured one Tuffy Truesdale throwing down against an 8-foot, 350-pound alligator.

Making way for a different kind of four wheels

Following World War II, there was a tremendous explosion in suburban development. More people were leaving Detroit and moving to newly built houses further from the city center. Indeed, Detroit’s population would decrease every year for more than half a century starting in 1950, dropping by 1.2 million (65 percent) between then and 2024. This exodus led to the creation of freeways that would enable people to get in and out of the city faster - and with Detroit having been built border to border, that meant plowing through neighborhoods and commercial corridors.

On Oct. 10, 1952, it was announced that the State Highway Commission had bought the Arena Gardens in order to tear it down to make way for the Edsel Ford Expressway (Interstate-94). The final competition held at the Arena Gardens was the state rollerskating championships, which got under way April 7, 1953. More than 300 skaters signed up to compete. A final rink reunion was held for members of the skating club on April 29.

That same month, the Michigan Highway Department awarded a demolition contract to take down the Gardens.

The Arena Gardens closed for good on May 3, 1953. The demolition permit was pulled that July 10, and began shortly after. The rink’s passing marked the end of an era in Detroit and in American rollerskating.

The Detroit News asked Martin whether he would build another rink elsewhere, and he said that the cost would be too high and that the Arena Gardens’ magic could not be duplicated.

Today, cars zoom across the site instead of rollerskaters. With fewer and fewer veterans of the Arena Gardens still around today, there is little to remind folks of the legendary roller rink that helped give rise to one of the country’s biggest fads and the building that put tens of thousands of Detroiters on a different type of four wheels.

Ahhhhhhh!!!! I love this Dan! 🫶🫶

I think this is my favorite Historic Detroit article yet! I'd never heard of the Arena Gardens before. What a fascinating life it had. Thanks for sharing its story.