The terror of the Great Lakes: The S.S. Aquarama

Folks called the cruise liner the 'Aquarammer' because she apparently had a vendetta against piers, docks, other ships and even small children

Ever since riding the Boblo boats as a kid, I’ve had a thing for ships.

At the beginning of the 20th century, Detroiters did, too. The Detroit River and Great Lakes used to have a ton of them, whether they be freighters hauling ore from the Upper Peninsula down to Detroit’s factories, or massive, smoke-belching passenger steamers shuttling folks around the Midwest in an era before airplane travel or highways.

I became obsessed with the Detroit & Cleveland Navigation Co.'s line of passenger steamers, some of which were more than 500 feet long - or about as long as a 50-story skyscraper is tall. Passengers would get on in Detroit in the evening, eat dinner and then stay the night in their cabin before waking up the next morning in Cleveland or Buffalo, N.Y., or Mackinac Island, Mich. They were the floating palaces of the Great Lakes, decked to the nines with fancy woodwork, stained glass and ornate plasterwork. You can still see this glamour for yourself at the Dossin Great Lakes Museum on Belle Isle, where the Gothic Room was saved from one of the D&C ships, the City of Detroit III.

But we’re not here to talk about anything nearly that elegant. In fact, we’re going to talk about a Great Lakes cruise liner that was the exact opposite in almost every way.

My friends, say hello to the S.S. Aquarama, the pinnacle of 1950s cruising splendor and the sworn enemy of every dock, wharf or pier between Detroit and Cleveland.

The D&C line had stopped running in 1950 after being unable to keep maritime passenger travel alive in the era of the automobile. After all, a giant, coal-gobbling steamship costs the same amount to run empty as it does full. Nevertheless, just three years after the D&C folded, some folks decided to give Great Lakes cruising another go, anyway.

In 1953, the Sand Products Co. of Detroit took a decommissioned World War II troop transport and converted it into a cruise ship to run between Detroit and Cleveland. The vessel had originally been named the Marine Star, and was launched in 1945 in Chester, Pa. The conversion was a two-year endeavor completed in Muskegon, Mich., at a cost of $8 million, the equivalent of a whopping $94 million in 2024, when adjusted for inflation. Rechristened the Aquarama, she would be the first new passenger liner on the Great Lakes in some two decades.

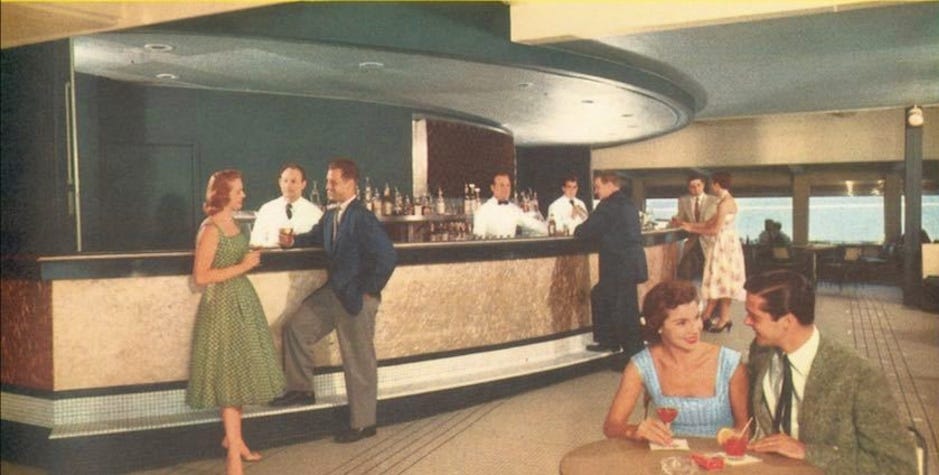

When she entered the circuit in 1956, the Aquarama offered live entertainment, five bars, four restaurants, a movie theater, a child’s playroom, a pair of dance floors, soda fountains, and other amenities. Ticket prices ranged from $2.50 to $4.75, or about $28 to $54 in 2024 valuation. Detroiters would board near Hart Plaza, where the D&C steamers once tied up.

At 520 feet long, the nine-deck Aquarama was one of the largest passenger ships to ever operate on the Great Lakes, and could carry up to 2,500 passengers and more than 150 cars. She had a single-screw, turbine-propelled, oil-fired engine that could propel her at 22 knots, the equivalent of about 25 miles per hour. The voyage from Detroit to Cleveland took about six hours, though as a promotional brochure noted, the "auto short-cut across Lake Erie ... saves 180 driving miles."

For its first year sailing the Great Lakes, the Aquarama was captained by 67-year-old Robert Leng, a 44-year veteran of the inland seas who had been called out of retirement. This was hardly a “noob,” as the kids say.

But not even a seasoned seaman could tame the Aquarama. The ship quickly developed a reputation for being an uncontrollable beast, earning the nicknames “Awkward Ram 'Em,” "Aquarammer" and "Crusherama" after a series of unfortunate run-ins.

She clobbered a dock minutes after getting under way on her first day out of Muskegon. A few months later, she backed into a seawall on the Detroit River in Windsor. Her second year wasn't without incident, either, when she ran into a dock in Cleveland in June 1956, damaging her bow. Just a week later, the Aquarama plowed into the Detroit News dock on West Jefferson and what is now Rosa Parks Boulevard. She also bumped a U.S. Navy cruiser near Cleveland, and was accused of nearly drowning a 2-year-old girl in 1957 with its gigantic wake at an Amherstburg, Ontario, beach.

The issue was that this leviathan was designed to handle the ocean seas. In the calmer waters of the Great Lakes, Detroit River and other environs, she was a bull in a china shop. And when she wasn't loaded down, the Aquarama sat too high in the water and could fall victim to winds and currents. Another problem laid in her single rear propeller, which didn't provide the finesse needed to maneuver close quarters at Great Lakes docks.

Her career would be short-lived, lasting from only 1955 to 1962. But considering that, as the Marine Star, she made just one trip across the Atlantic before World War II came to a close, her cruise line days were lengthy by comparison.

In the end, her maneuverability wasn't what did her in - it was that there just wasn’t enough demand for water travel between Detroit and Cleveland. The Aquarama made its last trip on Sept. 4, 1962.

She would sit rusting away back in Muskegon, Mich., for more than 25 years.

The Muskegon Chronicle reported April 10, 1983, that a group was allowed to tour the rusting ship.

“The ship’s exterior has obviously weathered a bit,” the paper wrote, “but inside and below decks, the group found the Aquarama just as it was in the 1950s — its furnishings and fixtures well protected from dust and mildew, its paint still bright. The tour itself was like a trip into the last generation: It was as though the crew had been gone for a week, rather than 20 years.”

It seemed that four years after that tour, the Aquarama had found a savior - or 23 of them, to be more precise.

Businessman James Everatt and 22 other investors bought the Aquarama for a rumored $3 million in 1987, worth about $8.2 million in 2024. Considering she was valued at only about $1 million in scrap value and had been mothballed for 24 years, the group may have overpaid. You can see video footage of her in Muskegon in 1987 here.

The investors originally proposed to turn her into a giant, floating casino on Detroit's riverfront, however, those dreams were dashed when voters shot down legalizing gambling in the 1980s. They had the Aquarama towed from Muskegon to Windsor, Ontario, in 1988, where she was squeezed into a rented slip barely big enough to hold her. The group then planned to make her a floating convention center, the centerpiece of a waterfront revitalization in Port Stanley, Ontario, but that failed to materialize, too. Meanwhile, the group of investors was paying $400,000 a year for the slip, which would be about $1 million a year in 2024. During her time docked in Windsor, the Aquarama was frequently targeted by vandals who smashed her windows and tagged their names around the ship. Meanwhile, Everatt's group removed most of the original 1950s furnishings, effectively gutting her ahead of the planned conversion.

Eight years after buying the Aquarama, a majority of the group was fed up with coughing up so much money with no return coming back. The group sold the Aquarama to Delaware-based Empire Cruise Lines, which Everatt owned a stake in. Everatt had yet another idea, though not entirely a new one. This time, he wanted to convert her into the largest casino ship in North America. It was supposed to take two years and cost $30 million to $50 million, the equivalent of $61.1 million to $101.8 million in 2024. He just needed to get her out of Ontario.

A backhoe was needed to dig out the Aquarama's anchor, which had become buried 15 feet below the riverbed after sitting in place for so long. But on Aug. 1, 1995, the Aquarama was on her way from Windsor to Buffalo, N.Y., arriving two days later.

Windsor harbor master Rod Beaton quipped to The Windsor Star for an Aug. 2, 1995, article about the Aquarama's departure: "It looked like hell, and right now it's the ugliest pile of junk. ... It should already have been recycled through three Toyotas now."

For the next 12 years, she was berthed at the Cargill Pool Elevator in Buffalo. Finally, two decades after Everatt and his associates bought her, the plug was pulled. The Aquarama was hauled across the Atlantic, arriving in Aliaga, Turkey, on Aug. 10, 2007, where she was mercifully carved up.

Despite being 62 years old at the time, she spent only eight years actually sailing under her own power.

Did you ever sail on the Aquarama? Tell us in the comments. And while you’re there, consider subscribing for more free Detroit history in your inbox and browser.

I remember the stories of her errant ways. Thanks for completing the saga.

Fascinating! Thank you.